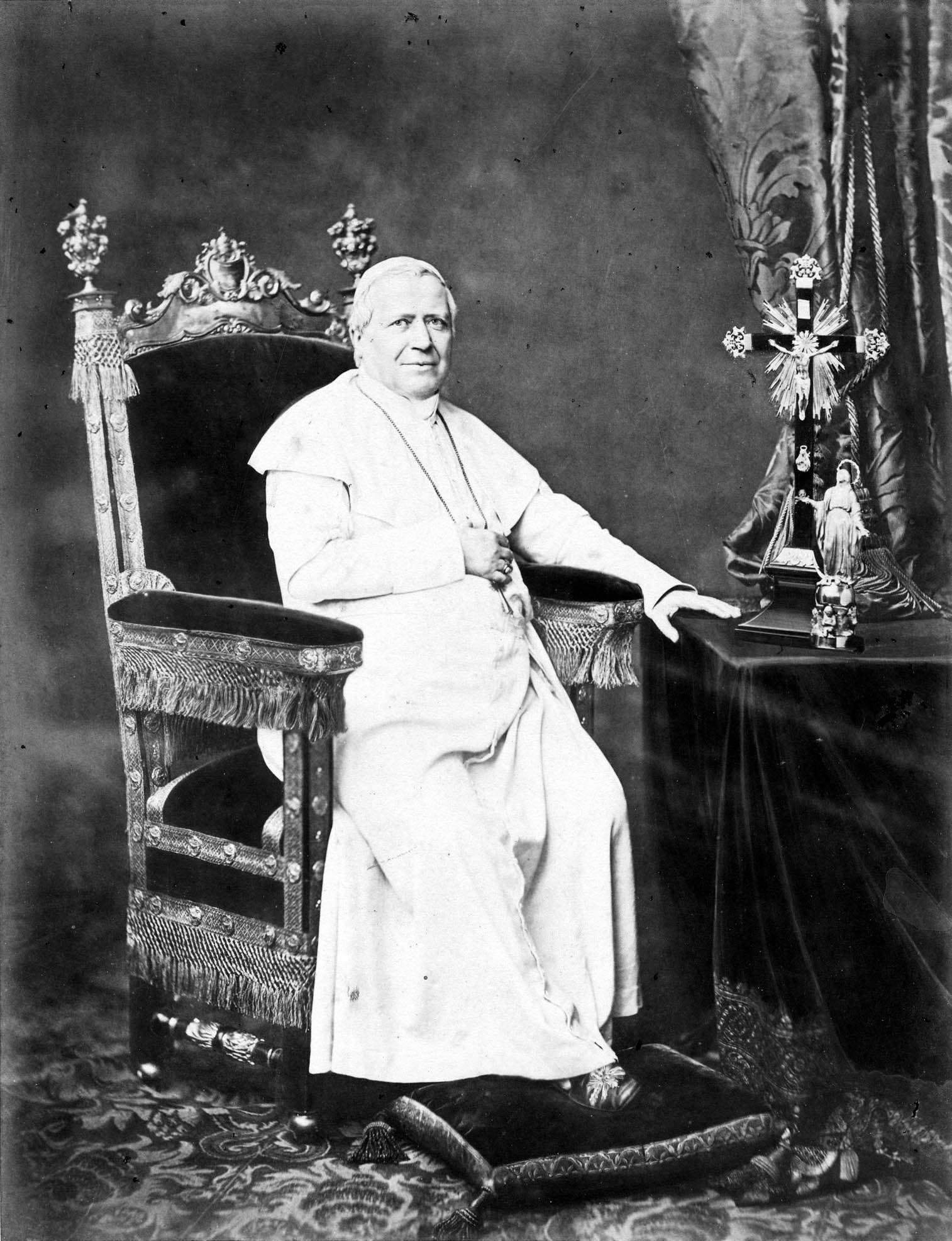

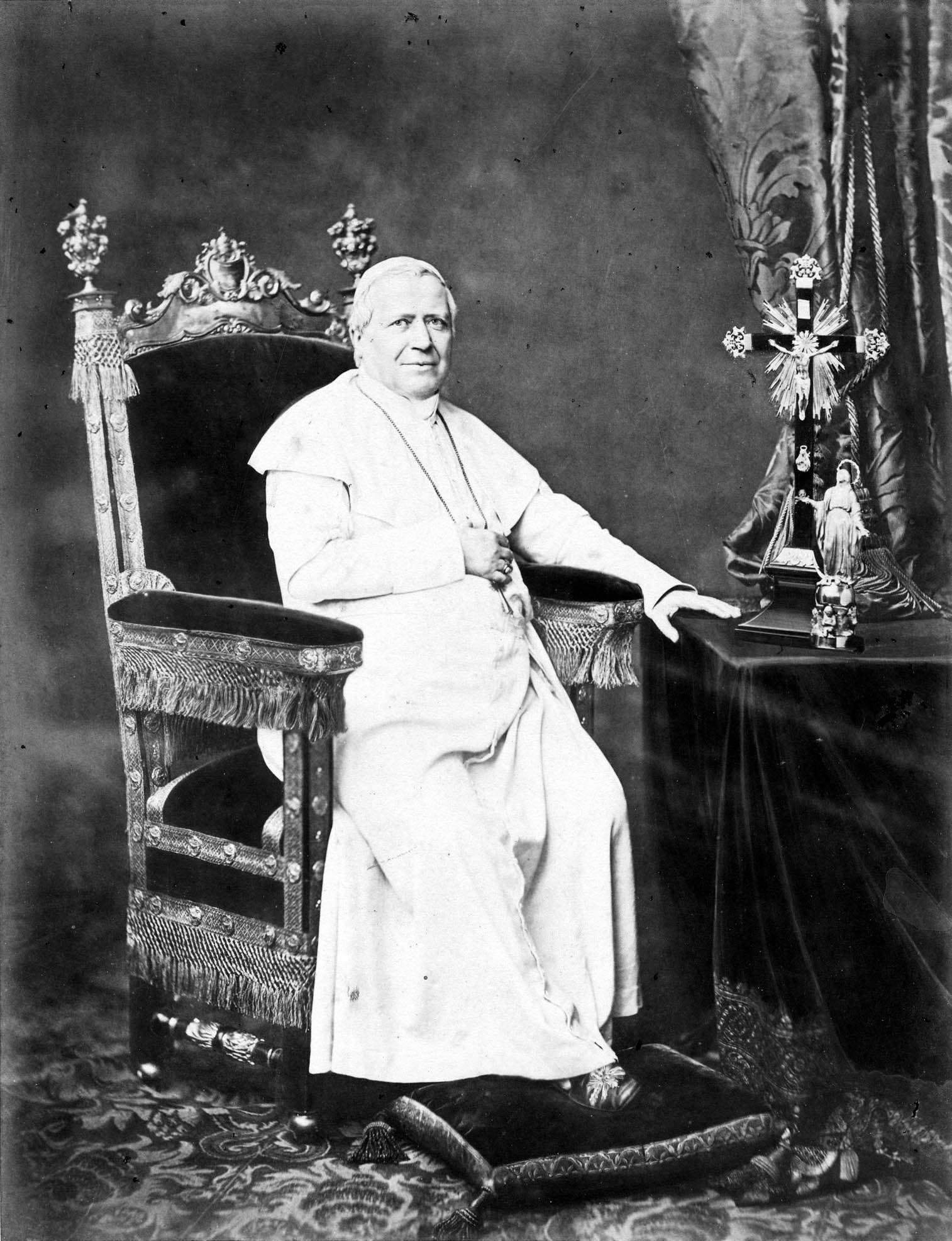

Pope Pius IX (; born Giovanni Maria Battista Pietro Pellegrino Isidoro Mastai-Ferretti; 13 May 1792 – 7 February 1878) was head of the

Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

from 1846 to 1878. His reign of nearly 32 years is the longest verified of any

pope

The pope is the bishop of Rome and the Head of the Church#Catholic Church, visible head of the worldwide Catholic Church. He is also known as the supreme pontiff, Roman pontiff, or sovereign pontiff. From the 8th century until 1870, the po ...

in history; if including unverified reigns, his reign was second to that of

Peter the Apostle

Saint Peter (born Shimon Bar Yonah; 1 BC – AD 64/68), also known as Peter the Apostle, Simon Peter, Simeon, Simon, or Cephas, was one of the Twelve Apostles of Jesus and one of the first leaders of the early Christian Church. He appears repe ...

. He was notable for convoking the

First Vatican Council

The First Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, commonly known as the First Vatican Council or Vatican I, was the 20th ecumenical council of the Catholic Church, held three centuries after the preceding Council of Trent which was adjourned in 156 ...

in 1868 and for permanently losing control of the

Papal States

The Papal States ( ; ; ), officially the State of the Church, were a conglomeration of territories on the Italian peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope from 756 to 1870. They were among the major states of Italy from the 8th c ...

in 1870 to the

Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy (, ) was a unitary state that existed from 17 March 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 10 June 1946, when the monarchy wa ...

. Thereafter, he refused to leave

Vatican City

Vatican City, officially the Vatican City State (; ), is a Landlocked country, landlocked sovereign state and city-state; it is enclaved within Rome, the capital city of Italy and Bishop of Rome, seat of the Catholic Church. It became inde ...

, declaring himself a "

prisoner in the Vatican

A prisoner in the Vatican (; ) or prisoner of the Vatican described the situation of the pope with respect to the Kingdom of Italy during the period from the capture of Rome by the Royal Italian Army on 20 September 1870 until the Lateran Treaty ...

".

At the time of his election, he was a liberal reformer, but his approach changed after the

Revolutions of 1848

The revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the springtime of the peoples or the springtime of nations, were a series of revolutions throughout Europe over the course of more than one year, from 1848 to 1849. It remains the most widespre ...

. Upon the assassination of his prime minister,

Pellegrino Rossi

Pellegrino Luigi Odoardo Rossi (13 July 1787 – 15 November 1848) was an Italian economist, politician and jurist. He was an important figure of the July Monarchy in France, and the minister of justice in the government of the Papal States, unde ...

, Pius fled

Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

and

excommunicated

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to deprive, suspend, or limit membership in a religious community or to restrict certain rights within it, in particular those of being in communion with other members of the con ...

all participants in the short-lived

Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( ) was the era of Ancient Rome, classical Roman civilisation beginning with Overthrow of the Roman monarchy, the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom (traditionally dated to 509 BC) and ending in 27 BC with the establis ...

. After its suppression by the French army and his return in 1850, his policies and doctrinal pronouncements became increasingly conservative. He was responsible for the

kidnapping of Edgardo Mortara, a six-year-old taken by force from his Jewish family who went on to become a Catholic priest in his own right and unsuccessfully attempted to convert his Jewish parents.

In his 1849

encyclical

An encyclical was originally a circular letter sent to all the churches of a particular area in the ancient Roman Church. At that time, the word could be used for a letter sent out by any bishop. The word comes from the Late Latin (originally fr ...

''

Ubi primum'', he emphasized

Mary's role in salvation. In 1854, he promulgated the dogma of the

Immaculate Conception

The Immaculate Conception is the doctrine that the Virgin Mary was free of original sin from the moment of her conception. It is one of the four Mariology, Marian dogmas of the Catholic Church. Debated by medieval theologians, it was not def ...

, articulating a long-held Catholic belief that Mary, the Mother of God, was conceived without

original sin

Original sin () in Christian theology refers to the condition of sinfulness that all humans share, which is inherited from Adam and Eve due to the Fall of man, Fall, involving the loss of original righteousness and the distortion of the Image ...

. His 1864 ''

Syllabus of Errors

The Syllabus of Errors is the name given to an index document issued by the Holy See under Pope Pius IX on 8 December 1864 at the same time as his encyclical letter . It collected a total of 80 propositions that the Pope considered to be curren ...

'' was a strong condemnation of liberalism,

modernism

Modernism was an early 20th-century movement in literature, visual arts, and music that emphasized experimentation, abstraction, and Subjectivity and objectivity (philosophy), subjective experience. Philosophy, politics, architecture, and soc ...

,

moral relativism

Moral relativism or ethical relativism (often reformulated as relativist ethics or relativist morality) is used to describe several Philosophy, philosophical positions concerned with the differences in Morality, moral judgments across different p ...

,

secularization

In sociology, secularization () is a multilayered concept that generally denotes "a transition from a religious to a more worldly level." There are many types of secularization and most do not lead to atheism or irreligion, nor are they automatica ...

,

separation of church and state

The separation of church and state is a philosophical and Jurisprudence, jurisprudential concept for defining political distance in the relationship between religious organizations and the State (polity), state. Conceptually, the term refers to ...

, and other

Enlightenment

Enlightenment or enlighten may refer to:

Age of Enlightenment

* Age of Enlightenment, period in Western intellectual history from the late 17th to late 18th century, centered in France but also encompassing (alphabetically by country or culture): ...

ideas.

His appeal for financial support revived global donations known as

Peter's Pence

Peter's Pence (or ''Denarii Sancti Petri'' and "Alms of St Peter") are donations or payments made directly to the Holy See of the Catholic Church. The practice began under the Saxons in Kingdom of England, England and spread through Europe. Both ...

. He strengthened the central power of the

Holy See

The Holy See (, ; ), also called the See of Rome, the Petrine See or the Apostolic See, is the central governing body of the Catholic Church and Vatican City. It encompasses the office of the pope as the Bishops in the Catholic Church, bishop ...

and

Roman Curia

The Roman Curia () comprises the administrative institutions of the Holy See and the central body through which the affairs of the Catholic Church are conducted. The Roman Curia is the institution of which the Roman Pontiff ordinarily makes use ...

over the worldwide Catholic Church, while also formalizing the pope's ultimate doctrinal authority (the dogma of

papal infallibility

Papal infallibility is a Dogma in the Catholic Church, dogma of the Catholic Church which states that, in virtue of the promise of Jesus to Saint Peter, Peter, the Pope when he speaks is preserved from the possibility of error on doctrine "in ...

defined in 1870).

Pope John Paul II

Pope John Paul II (born Karol Józef Wojtyła; 18 May 19202 April 2005) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 16 October 1978 until Death and funeral of Pope John Paul II, his death in 2005.

In his you ...

beatified him in 2000.

Early life and ministry

Giovanni Maria Mastai-Ferretti was born on 13 May 1792 in

Senigallia

Senigallia (or Sinigaglia in Old Italian; ) is a ''comune'' (municipality) and port town on Italy's Adriatic Sea, Adriatic coast. It is situated in the province of Ancona, in the Italian region of Marche, and lies approximately 30 kilometres nor ...

. He was the ninth child born into the noble family of Girolamo dei Conti Mastai-Ferretti (1750–1833), grandnephew of

Pietro Girolamo Guglielmi, and wife Caterina Antonia Maddalena Solazzei di Fano (1764–1842). He was baptized on the day of his birth with the names Giovanni Maria Battista Pietro Pellegrino Isidoro. He was educated at the

Piarist

The Piarists (), officially named the Order of Poor Clerics Regular of the Mother of God of the Pious Schools (), abbreviated SchP, is a religious order of clerics regular of the Catholic Church founded in 1617 by Spanish priest Joseph Calasanz ...

College in

Volterra

Volterra (; Latin: ''Volaterrae'') is a walled mountaintop town in the Tuscany region of Italy. Its history dates from before the 8th century BC and it has substantial structures from the Etruscan, Roman, and Medieval periods.

History

...

and in Rome. An unreliable account published many years later suggests that the young Count Mastai was engaged to the daughter of the Protestant

Church of Ireland

The Church of Ireland (, ; , ) is a Christian church in Ireland, and an autonomy, autonomous province of the Anglican Communion. It is organised on an all-Ireland basis and is the Christianity in Ireland, second-largest Christian church on the ...

Bishop of Kilmore,

William Foster. If there was ever any such engagement, it did not proceed.

In 1814, as a theology student in his hometown of Sinigaglia, he met

Pope Pius VII

Pope Pius VII (; born Barnaba Niccolò Maria Luigi Chiaramonti; 14 August 1742 – 20 August 1823) was head of the Catholic Church from 14 March 1800 to his death in August 1823. He ruled the Papal States from June 1800 to 17 May 1809 and again ...

, who had returned from French captivity. In 1815, he entered the Papal

Noble Guard

The Noble Guard () was one of the household guard units serving the Pope, and formed part of the military in Vatican City. It was formed by Pope Pius VII in 1801 as a regiment of heavy cavalry, and abolished in 1970 by Pope Paul VI following Vat ...

but was soon dismissed after an epileptic seizure.

He threw himself on the mercy of Pius VII, who elevated him and supported his continued theological studies.

Mastai-Ferretti was ordained a priest on 10 April 1819. The Pope had originally insisted that another priest should assist Mastai-Ferretti during Holy Mass, but rescinded the stipulation after the seizures became less frequent. He initially worked as the rector of the Tata Giovanni Institute in Rome.

Shortly before his death, Pius VII – following Chilean leader

Bernardo O'Higgins

Bernardo O'Higgins Riquelme (; 20 August 1778 – 24 October 1842) was a Chilean independence leader who freed Chile from Spanish rule in the Chilean War of Independence. He was a wealthy landowner of Basque people, Basque-Spanish people, Spani ...

' wish to have the Pope reorganize the Catholic Church of the new republic – named him

auditor

An auditor is a person or a firm appointed by a company to execute an audit.Practical Auditing, Kul Narsingh Shrestha, 2012, Nabin Prakashan, Nepal To act as an auditor, a person should be certified by the regulatory authority of accounting an ...

to assist the

apostolic nuncio

An apostolic nuncio (; also known as a papal nuncio or simply as a nuncio) is an ecclesiastical diplomat, serving as an envoy or a permanent diplomatic representative of the Holy See to a state or to an international organization. A nuncio is ...

, Monsignore Giovanni Muzi, in the first mission to post-revolutionary South America. The mission had the objective to map out the role of the

Catholic Church in Chile

The Catholic Church in Chile is part of the worldwide Catholic Church, under the spiritual leadership of the Pope, the curia in Rome, and the Episcopal Conference of Chile.

The Church is composed of 5 archdioceses, 18 dioceses, 2 territor ...

and its relationship with the state, but when it finally arrived in

Santiago

Santiago (, ; ), also known as Santiago de Chile (), is the capital and largest city of Chile and one of the largest cities in the Americas. It is located in the country's central valley and is the center of the Santiago Metropolitan Regi ...

in March 1824, O'Higgins had been overthrown and replaced by General

Ramón Freire

Ramón Saturnino Andrés Freire y Serrano (; November 29, 1787 – December 9, 1851) was a Chilean political figure. He was head of state on several occasions, and enjoyed a numerous following until the War of the Confederation. Ramón Fr ...

, who was less well-disposed toward the Church and had already taken hostile measures such as the seizure of Church property. Having ended in failure, the mission returned to Europe. Nevertheless, Mastai-Ferretti had been the first future pope ever to have been in the Americas. Upon his return to Rome, the successor of Pius VII,

Pope Leo XII

Pope Leo XII (; born Annibale Francesco Clemente Melchiorre Girolamo Nicola della Genga; 2 August 1760 – 10 February 1829) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 28 September 1823 to his death in February 1829. ...

, appointed him head of the hospital of

San Michele a Ripa in Rome (1825–1827) and

canon

Canon or Canons may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Canon (fiction), the material accepted as officially written by an author or an ascribed author

* Literary canon, an accepted body of works considered as high culture

** Western canon, th ...

of

Santa Maria in Via Lata

Santa Maria in Via Lata is a church on the Via del Corso (the ancient Via Lata), in Rome, Italy. It stands diagonal from the church of San Marcello al Corso. It is the stational church for Tuesday in the fifth week of lent.

History

The first ...

.

Leo XII appointed the 35-year-old Mastai-Ferretti

Archbishop of Spoleto in 1827. In 1831, the

abortive revolution that had begun in

Parma

Parma (; ) is a city in the northern Italian region of Emilia-Romagna known for its architecture, Giuseppe Verdi, music, art, prosciutto (ham), Parmesan, cheese and surrounding countryside. With a population of 198,986 inhabitants as of 2025, ...

and

Modena

Modena (, ; ; ; ; ) is a city and ''comune'' (municipality) on the south side of the Po Valley, in the Province of Modena, in the Emilia-Romagna region of northern Italy. It has 184,739 inhabitants as of 2025.

A town, and seat of an archbis ...

spread to

Spoleto

Spoleto (, also , , ; ) is an ancient city in the Italian province of Perugia in east-central Umbria on a foothill of the Apennines. It is south of Trevi, north of Terni, southeast of Perugia; southeast of Florence; and north of Rome.

H ...

; the Archbishop obtained a general pardon after it was suppressed, gaining him a reputation for being liberal. During an earthquake, he made a reputation as an efficient organizer of relief and great charity. The following year he was moved to the more prestigious

Diocese of Imola, was made a

cardinal

Cardinal or The Cardinal most commonly refers to

* Cardinalidae, a family of North and South American birds

**''Cardinalis'', genus of three species in the family Cardinalidae

***Northern cardinal, ''Cardinalis cardinalis'', the common cardinal of ...

''in pectore'' in 1839, and in 1840 was publicly announced as

cardinal-priest

A cardinal is a senior member of the clergy of the Catholic Church. As titular members of the clergy of the Diocese of Rome, they serve as advisors to the pope, who is the bishop of Rome and the visible head of the worldwide Catholic Church. ...

of

Santi Marcellino e Pietro al Laterano

Santi Marcellino e Pietro al Laterano is a Roman catholic parish and titular church in Rome on the Via Merulana. One of the oldest churches in Rome, it is dedicated to Saints Marcellinus and Peter, 4th century Roman martyrs, whose relics wer ...

. As in Spoleto, his episcopal priorities were the formation of priests through improved education and charities. He became known for visiting prisoners in jail and for programs for street children. Cardinal Mastai-Ferretti was considered a liberal during his episcopate in Spoleto and Imola because he supported administrative changes in the

Papal States

The Papal States ( ; ; ), officially the State of the Church, were a conglomeration of territories on the Italian peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope from 756 to 1870. They were among the major states of Italy from the 8th c ...

and sympathized with the nationalist movement in Italy.

Election

The

conclave

A conclave is a gathering of the College of Cardinals convened to appoint the pope of the Catholic Church. Catholics consider the pope to be the apostolic successor of Saint Peter and the earthly head of the Catholic Church.

Concerns around ...

of 1846, following the death of

Pope Gregory XVI

Pope Gregory XVI (; ; born Bartolomeo Alberto Cappellari; 18 September 1765 – 1 June 1846) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 2 February 1831 to his death in June 1846. He had adopted the name Mauro upon enteri ...

(1831–1846), took place in an unsettled political climate within Italy. The conclave was steeped in a factional division between right and left. The conservatives on the right favoured the hardline stances and

papal absolutism of the previous pontificate, while liberals supported moderate reforms. The conservatives supported

Luigi Lambruschini

Luigi Lambruschini (6 March 1776 – 12 May 1854) was an Italian cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church in the mid nineteenth century. He was a member of the Clerics Regular of St. Paul and served in the diplomatic corps of the Holy See.

Biograp ...

, the late pope's

Cardinal Secretary of State

The Secretary of State of His Holiness (; ), also known as the Cardinal Secretary of State or the Vatican Secretary of State, presides over the Secretariat of State of the Holy See, the oldest and most important dicastery of the Roman Curia. Th ...

. Liberals supported two candidates:

Tommaso Pasquale Gizzi and the then 54-year-old Mastai Ferretti.

During the first ballot, Mastai-Ferretti received 15 votes, the rest going to Lambruschini and Gizzi. Lambruschini received a majority of the votes in the early ballots but failed to achieve the required two-thirds majority. Gizzi was favoured by the

French government

The Government of France (, ), officially the Government of the French Republic (, ), exercises Executive (government), executive power in France. It is composed of the Prime Minister of France, prime minister, who is the head of government, ...

but failed to get further support from the cardinals, and the conclave ended up ultimately as a contest between Lambruschini and Mastai-Ferretti.

In the meantime, Cardinal

Tommaso Bernetti

Tommaso Bernetti (29 December 1779 – 21 March 1852) was an Italian people, Italian Roman Catholic Church, Roman Catholic prelate and Cardinal (Catholic Church), cardinal who served in the Secretariat of State (Holy See), Secretariat of State an ...

reportedly received information that Cardinal

Karl Kajetan von Gaisruck

Karl Kajetan von Gaisruck (Italian: Carlo Gaetano (di) Gaisruck) (1769–1846) was an Austrian Cardinal and the archbishop of Milan from 1816 to 1846. He also held the title of ''Graf'' or Count.

Early life

Gaisruck was born on 7 August 1769 in ...

, the Austrian Archbishop of Milan, was on his way to the conclave to

veto

A veto is a legal power to unilaterally stop an official action. In the most typical case, a president (government title), president or monarch vetoes a bill (law), bill to stop it from becoming statutory law, law. In many countries, veto powe ...

the election of Mastai-Ferretti on behalf of the

Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire, officially known as the Empire of Austria, was a Multinational state, multinational European Great Powers, great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the Habsburg monarchy, realms of the Habsburgs. Duri ...

and

Prince Metternich. According to historian Valérie Pirie, Bernetti realized that he had only a few hours in which to stop Lambruschini's election.

Faced with a deadlock and urgently persuaded by Bernetti to reject Lambruschini, liberals and moderates decided to cast their votes for Mastai-Ferretti, in a move that contradicted the general mood throughout Europe. On the evening of the second day of the conclave, 16 June 1846, Mastai-Ferretti was elected pope. "He was a glamorous candidate, ardent, emotional with a gift for friendship and a track-record of generosity even towards anti-Clericals and

Carbonari

The Carbonari () was an informal network of Secret society, secret revolutionary societies active in Italy from about 1800 to 1831. The Carbonari may have further influenced other revolutionary groups in France, Portugal, Spain, Brazil, Urugua ...

. He was a patriot, known to be critical of Gregory XVI." Because it was night, no formal announcement was given, just the signal of white smoke.

On the following morning, the Cardinal

protodeacon

Protodeacon derives from the Greek ''proto-'' meaning 'first' and ''diakonos'', which is a standard ancient Greek word meaning "assistant", "servant", or "waiting-man". The word in English may refer to any of various clergy, depending upon the usa ...

,

Tommaso Riario Sforza

Tommaso Riario Sforza (8 January 1782 in Naples – 14 March 1857 in Rome) was the Neapolitan Cardinal (Catholicism), Cardinal who, as protodeacon, announced at the end of the 1846 Papal conclave, conclave the election of Cardinal Giovann ...

, announced the election of Mastai Ferretti before a crowd of faithful Catholics. When Mastai-Ferretti appeared on the balcony, the mood became joyous. He chose the name of Pius IX in honour of

Pope Pius VII

Pope Pius VII (; born Barnaba Niccolò Maria Luigi Chiaramonti; 14 August 1742 – 20 August 1823) was head of the Catholic Church from 14 March 1800 to his death in August 1823. He ruled the Papal States from June 1800 to 17 May 1809 and again ...

, who had encouraged his vocation to the priesthood despite his childhood epilepsy. However, the new pope had little diplomatic experience and no curial experience at all. Pius IX was crowned on 21 June 1846.

The election of the liberal Pius IX created much enthusiasm in Europe and elsewhere. "For the next twenty months after the election, Pius IX was the most popular man on the Italian peninsula, where the exclamation "Long life to Pius IX!" was often heard.

English Protestants celebrated him as a "friend of light" and a reformer of

Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

towards freedom and progress. He was elected without secular political influences and in the full vigor of life. He was pious, progressive, intellectual, decent, friendly, and open to all. While his political views and policies were hotly debated in the coming years, his personal lifestyle was above reproach, a model of simplicity and poverty in everyday affairs.

Papacy

Cardinal Mastai Ferretti entered the papacy in 1846, amidst widespread expectations that he would be a champion of reform and modernization in the Papal States, which he ruled directly, and in the entire Catholic Church. Admirers wanted him to lead the battle for Italian independence. His later turn toward profound conservatism shocked and dismayed his original supporters, while surprising and delighting the conservative old guard.

Centralization of the church

The most notable event in Pius IX's long pontificate was the end of the

Papal States

The Papal States ( ; ; ), officially the State of the Church, were a conglomeration of territories on the Italian peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope from 756 to 1870. They were among the major states of Italy from the 8th c ...

, which lay in the middle of the "Italian boot" around the central area of

Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

. In contrast, he led the worldwide Church toward an ever-increasing centralization and consolidation of power in Rome and the papacy. More than his predecessors, Pius used the papal pulpit to address the bishops of the world. The

First Vatican Council

The First Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, commonly known as the First Vatican Council or Vatican I, was the 20th ecumenical council of the Catholic Church, held three centuries after the preceding Council of Trent which was adjourned in 156 ...

(1869–1870), which he convened to consolidate papal authority further, was considered a milestone not only in his pontificate but also in ecclesiastical history through its defining of the dogma of

papal infallibility

Papal infallibility is a Dogma in the Catholic Church, dogma of the Catholic Church which states that, in virtue of the promise of Jesus to Saint Peter, Peter, the Pope when he speaks is preserved from the possibility of error on doctrine "in ...

.

Dispute with the Melkite Greek Catholic Church

After the

First Vatican Council

The First Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, commonly known as the First Vatican Council or Vatican I, was the 20th ecumenical council of the Catholic Church, held three centuries after the preceding Council of Trent which was adjourned in 156 ...

concluded, an emissary of the Roman Curia was dispatched to secure the signatures of Patriarch

Gregory II Youssef and the rest of the

Melkite

The term Melkite (), also written Melchite, refers to various Eastern Christian churches of the Byzantine Rite and their members originating in West Asia. The term comes from the common Central Semitic root ''m-l-k'', meaning "royal", referrin ...

delegation who had voted ''non placet'' at the general congregation and left Rome prior to the adoption of the dogmatic constitution ''

Pastor aeternus

''Pastor aeternus'' ("First dogmatic constitution, Dogmatic Constitution on the Church of Christ") was issued by the First Vatican Council, July 18, 1870. The document defines four doctrines of the Catholic Church, Catholic faith: the Primacy of ...

'' on

papal infallibility

Papal infallibility is a Dogma in the Catholic Church, dogma of the Catholic Church which states that, in virtue of the promise of Jesus to Saint Peter, Peter, the Pope when he speaks is preserved from the possibility of error on doctrine "in ...

. Gregory and the Melkite bishops ultimately subscribed to it, but added the qualifying clause used at the

Council of Florence

The Council of Florence is the seventeenth ecumenical council recognized by the Catholic Church, held between 1431 and 1445. It was convened in territories under the Holy Roman Empire. Italy became a venue of a Catholic ecumenical council aft ...

: "except the rights and privileges of Eastern patriarchs." This earned Gregory the enmity of Pius IX; during his next visit to the

pontiff

In Roman antiquity, a pontiff () was a member of the most illustrious of the colleges of priests of the Roman religion, the College of Pontiffs."Pontifex". "Oxford English Dictionary", March 2007 The term ''pontiff'' was later applied to any h ...

, before leaving Rome, when Gregory was kneeling, Pius placed his knee on the patriarch's shoulder, just saying to him: ''Testa dura!'' (''You obstinate man!''). In spite of this event, Gregory and the

Melkite Greek Catholic Church

The Melkite Greek Catholic Church (, ''Kanīsat ar-Rūm al-Malakiyyīn al-Kāṯūlīk''; ; ), also known as the Melkite Byzantine Catholic Church, is an Eastern Catholic church in full communion with the Holy See as part of the worldwide Catho ...

remained committed to their union with the Holy See.

Ecclesiastical rights

The ecclesiastical policies of Pius IX were dominated by defence of the rights of the church and the free exercise of religion for Catholics in countries such as

Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

and the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

. He also fought against what he perceived to be anti-Catholic philosophies in countries such as

Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

,

Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

, and

France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

. The German Empire sought to

restrict and weaken the Church for a decade after the

Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the War of 1870, was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the North German Confederation led by the Kingdom of Prussia. Lasting from 19 July 1870 to 28 Janua ...

.

Jubilees

Pius IX celebrated several jubilees including the 300th anniversary of the

Council of Trent

The Council of Trent (), held between 1545 and 1563 in Trent (or Trento), now in northern Italy, was the 19th ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. Prompted by the Protestant Reformation at the time, it has been described as the "most ...

. Pius celebrated the 1,800th anniversary of the martyrdom of the

Apostle Peter

An apostle (), in its literal sense, is an emissary. The word is derived from Ancient Greek ἀπόστολος (''apóstolos''), literally "one who is sent off", itself derived from the verb ἀποστέλλειν (''apostéllein''), "to se ...

and

Apostle Paul

Paul, also named Saul of Tarsus, commonly known as Paul the Apostle and Saint Paul, was a Apostles in the New Testament, Christian apostle ( AD) who spread the Ministry of Jesus, teachings of Jesus in the Christianity in the 1st century, first ...

on 29 June 1867 with 512 bishops, 20,000 priests and 140,000 lay persons in Rome. A large gathering was organized in 1871 to commemorate the 25th anniversary of his papacy. Though the Italian government in 1870 outlawed many popular pilgrimages, the faithful of

Bologna

Bologna ( , , ; ; ) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in northern Italy. It is the List of cities in Italy, seventh most populous city in Italy, with about 400,000 inhabitants and 150 different nationalities. Its M ...

organized a nationwide "spiritual pilgrimage" to the pope and the tombs of the apostles in 1873. In 1875, Pius declared a

Holy Year

A jubilee is a special year of remission of sins, debts and universal pardon. In the Book of Leviticus, a jubilee year is mentioned as occurring every 50th year (after 49 years, 7x7, as per Leviticus 25:8) during which slaves and prisoners would ...

that was celebrated throughout the Catholic world. On the 50th anniversary of his episcopal consecration, people from all parts of the world came to see the old pontiff from 30 April 1877 to 15 June 1877. He was a bit shy, but he valued initiative within the church and created several new titles, rewards, and orders to elevate those who in his view deserved merit.

Consistories

Pius IX created 122 new cardinals, of whom 64 were alive at his death; at the time membership in the

College of Cardinals

The College of Cardinals (), also called the Sacred College of Cardinals, is the body of all cardinals of the Catholic Church. there are cardinals, of whom are eligible to vote in a conclave to elect a new pope. Appointed by the pope, ...

was limited to 70. Noteworthy elevations included Vincenzo Pecci (his eventual successor

Leo XIII

Pope Leo XIII (; born Gioacchino Vincenzo Raffaele Luigi Pecci; 2March 181020July 1903) was head of the Catholic Church from 20 February 1878 until his death in July 1903. He had the fourth-longest reign of any pope, behind those of Peter the A ...

);

Nicholas Wiseman

Nicholas Patrick Stephen Wiseman (3 August 1802 – 15 February 1865) was an English Roman Catholic prelate who served as the first Archbishop of Westminster upon the re-establishment of the Roman Catholic hierarchy in England and Wales in 1 ...

of Westminster; the convert

Henry Edward Manning

Henry Edward Manning (15 July 1808 – 14 January 1892) was an English prelate of the Catholic Church, and the second Archbishop of Westminster from 1865 until his death in 1892. He was ordained in the Church of England as a young man, but co ...

; and

John McCloskey

John McCloskey (March 10, 1810 – October 10, 1885) was an Catholic Church in the United States, American Catholic prelate who served as the first American-born Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New York, Archbishop of New York from 1864 until his ...

, the first American cardinal.

According to Bishop Cipriano Calderón, the pope intended to make the

Bishop of Michoacán,

Juan Cayetano Gómez de Portugal y Solís, a cardinal in 1850 and even had Cardinal

Giacomo Antonelli

Giacomo Antonelli (2 April 1806 – 6 November 1876) was an Italian Catholic prelate who served as Cardinal Secretary of State for the Holy See from 1848 until his death. He played a key role in Italian politics, resisting the unification o ...

send a letter to him to express his intentions. He would have been the first Latin American cardinal had he not died before the next consistory. According to the

Benedictine

The Benedictines, officially the Order of Saint Benedict (, abbreviated as O.S.B. or OSB), are a mainly contemplative monastic order of the Catholic Church for men and for women who follow the Rule of Saint Benedict. Initiated in 529, th ...

monk Guy-Marie Oury, a letter addressed by

Prosper Guéranger

Prosper Louis Pascal Guéranger (; 4 April 1805 – 30 January 1875) was a French priest and Benedictine monk, who served for nearly 40 years as the abbot of the monastery of Solesmes (which he founded among the ruins of a former priory at Sol ...

to his Benedictine colleague Léandre Fonteinne on 6 March 1856 indicated that Guéranger had learned that Pius IX wanted to name him a cardinal in November 1855, but he refused the honor because he did not want to live in Rome. As a result, Pius IX made the

Bishop of La Rochelle Clément Villecourt a cardinal instead.

On 22 August 1861, the pope informed the

Patriarch of Venice

The Patriarch of Venice (; ) is the ordinary of the Patriarchate of Venice. The bishop is one of only four patriarchs in the Latin Rite of the Catholic Church. The other three are the Patriarch of Lisbon, the Patriarch of the East Indies an ...

Angelo Ramazzotti that he would name him a cardinal, however, Ramazzoti died three days before the consistory. Also in 1861, the

dean of the Sacred Rota Ignazio Alberghini declined the pope's offer of nomination into the Sacred College. In December 1863, Pius IX intended to elevate the

Archbishop of Gniezno and Poznań Leon Michał Przyłuski to the cardinalate, but he died before the consistory took place. In 1866, Pius IX wanted to nominate a

Barnabite

The Barnabites (), officially named as the Clerics Regular of Saint Paul (), are a religious order of clerics regular founded in 1530 in the Catholic Church. They are associated with the Angelic Sisters of Saint Paul and the members of the Bar ...

to the College of Cardinals before he opened the First Vatican Council. While the pope originally decided on appointing

Carlo Vercellone

Carlo Vercellone (10 January 181419 January 1869) was an Italian biblical scholar.

Biography

Carlo was born at Biella. He entered the Order of the Barnabites at Genoa, in 1829; studied philosophy at Turin and theology at Rome, under Luigi Ungare ...

, a noted biblical scholar, Vercellone refused due to his precarious health, instead proposing that Pius IX instead nominate

Luigi Bilio

Luigi Maria Bilio (25 March 1826 – 30 January 1884), was a Cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church who, among other offices, was Secretary of the Supreme Sacred Congregation of the Holy Office.

Life

Bilio was born in Alessandria, Piedmont, I ...

. In 1868, Pius IX nominated Andre Pila to the cardinalate, however, he died the day before he would have been elevated as the only person for elevation in that April consistory. Also in 1868, Pius IX offered the cardinalate to the Bishop of Concepción

José Hipólito Salas whom he had met during the First Vatican Council, inviting him to join the Roman Curia. However, the bishop preferred to live in Chile and declined the offer, while Pius IX did not offer it again in the future.

[

In 1875, Pius IX intended to nominate the papal ]almoner

An almoner () is a chaplain or church officer who originally was in charge of distributing money to the deserving poor. The title ''almoner'' has to some extent fallen out of use in English, but its equivalents in other languages are often used f ...

Xavier de Mérode to the Sacred College, however, he died just eight months before the consistory was to be held. Pius IX also decided to nominate , a longtime Curial official, but he declined and instead joined the Society of Jesus

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rome. It was founded in 1540 ...

in mid-1874.[

]

Canonizations and beatifications

Pope Pius IX canonized

Canonization is the declaration of a deceased person as an officially recognized saint, specifically, the official act of a Christian communion declaring a person worthy of public veneration and entering their name in the canon catalogue of sa ...

52 saints during his pontificate. He canonized notable saints such as the Martyrs of Japan

The were Christians, Christian missionaries and followers who were persecuted and executed, mostly during the Tokugawa shogunate period in the 17th century. The Japanese saw the rituals of the Christians causing people to pray, close their eyes w ...

(8 June 1862), Josaphat Kuntsevych

Josaphat Kuntsevych, OSBM ( – 12 November 1623) was a Basilian hieromonk and archeparch of the Ruthenian Uniate Church who served as Archbishop of Polotsk from 1618 to 1623. On 12 November 1623, he was beaten to death with an axe ...

(29 June 1867), and Nicholas Pieck (29 June 1867). Pius IX further beatified

Beatification (from Latin , "blessed" and , "to make") is a recognition accorded by the Catholic Church of a deceased person's entrance into Heaven and capacity to intercede on behalf of individuals who pray in their name. ''Beati'' is the ...

222 individuals throughout his papacy, including the likes of Benedict Joseph Labre

Benedict Joseph Labre, TOSF (, 25 March 1748 – 16 April 1783) was a French Third Order of Saint Francis, Franciscan tertiary, and Catholic Church, Catholic saint. Labre was from a well-to-do family near Arras, France. After attempting a monasti ...

, Peter Claver

Peter Claver (; 26 June 1580 – 8 September 1654) was a Spanish Jesuit priest and missionary born in Verdú, Spain, who, due to his life and work, became the patron saint of slaves, Colombia, and ministry to African Americans.

During the 4 ...

, and his two predecessors Pope Eugene III

Pope Eugene III (; c. 1080 – 8 July 1153), born Bernardo Pignatelli, or possibly Paganelli, called Bernardo da Pisa, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 15 February 1145 to his death in 1153. He was the first Cist ...

and Pope Urban V

Pope Urban V (; 1310 – 19 December 1370), born Guillaume de Grimoard, was head of the Catholic Church from 28 September 1362 until his death, in December 1370 and was also a member of the Order of Saint Benedict. He was the only Avignon pope ...

.

Doctors of the Church

Pius IX named three new Doctors of the Church

Doctor of the Church (Latin: ''doctor'' "teacher"), also referred to as Doctor of the Universal Church (Latin: ''Doctor Ecclesiae Universalis''), is a title given by the Catholic Church to saints recognized as having made a significant contribut ...

: Hilary of Poitiers

Hilary of Poitiers (; ) was Bishop of Poitiers and a Doctor of the Church. He was sometimes referred to as the "Hammer of the Arians" () and the " Athanasius of the West". His name comes from the Latin word for happy or cheerful. In addition t ...

(13 May 1851, naming him "" or "Doctor of the Divinity of Christ"), Alphonsus Liguori

Alphonsus Maria de Liguori (27 September 1696 – 1 August 1787) was an Italian Catholic bishop and saint, as well as a spiritual writer, composer, musician, artist, poet, lawyer, scholastic philosopher, and theologian. He founded the Congre ...

(23 March 1871, naming him "" or "Most Zealous Doctor"), and Francis de Sales

Francis de Sales, Congregation of the Oratory, C.O., Order of Minims, O.M. (; ; 21 August 156728 December 1622) was a Savoyard state, Savoyard Catholic prelate who served as Bishop of Geneva and is a saint of the Catholic Church. He became n ...

(19 July 1877, naming him "" or "Doctor of Charity").

Sovereignty of the Papal States

Pius IX was not only pope but, until 1870, also the last sovereign

''Sovereign'' is a title that can be applied to the highest leader in various categories. The word is borrowed from Old French , which is ultimately derived from the Latin">-4; we might wonder whether there's a point at which it's appropriate to ...

ruler of the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; ; ), officially the State of the Church, were a conglomeration of territories on the Italian peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope from 756 to 1870. They were among the major states of Italy from the 8th c ...

. As a secular ruler he was occasionally referred to as "king", though it is unclear whether the Holy See

The Holy See (, ; ), also called the See of Rome, the Petrine See or the Apostolic See, is the central governing body of the Catholic Church and Vatican City. It encompasses the office of the pope as the Bishops in the Catholic Church, bishop ...

ever accepted this title. Ignaz von Döllinger

Johann Joseph Ignaz von Döllinger (; 28 February 179914 January 1890), also Doellinger in English, was a German theologian, Catholic priest and church historian who rejected the dogma of papal infallibility. Among his writings which proved c ...

, a fervent critic of Pius' infallibility dogma, considered the political regime of the pope in the Papal States "wise, well-intentioned, mild-natured, frugal and open for innovations". Yet there was controversy. In the period before the 1848 revolutions

The revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the springtime of the peoples or the springtime of nations, were a series of revolutions throughout Europe over the course of more than one year, from 1848 to 1849. It remains the most widespre ...

, Pius was a most ardent reformer advised by such innovative thinkers as Antonio Rosmini

Antonio Francesco Davide Ambrogio Rosmini-Serbati, IC (; 25 March 17971 July 1855) was an Italian Catholic priest and philosopher. He founded the Rosminians, officially the Institute of Charity, and pioneered the concept of social justice an ...

(1797–1855), who reconciled the new free-thinking concerning human rights with the classical natural law

Natural law (, ) is a Philosophy, philosophical and legal theory that posits the existence of a set of inherent laws derived from nature and universal moral principles, which are discoverable through reason. In ethics, natural law theory asserts ...

tradition of the church's political and economic teaching on social justice

Social justice is justice in relation to the distribution of wealth, opportunities, and privileges within a society where individuals' rights are recognized and protected. In Western and Asian cultures, the concept of social justice has of ...

. After the revolution, his political reforms and constitutional improvements were minimal, remaining largely within the framework of the 1850 laws mentioned above.

Reforms in the Papal States

Pius IX's liberal policies initially made him very popular throughout Italy. He appointed an able and enlightened minister, Pellegrino Rossi

Pellegrino Luigi Odoardo Rossi (13 July 1787 – 15 November 1848) was an Italian economist, politician and jurist. He was an important figure of the July Monarchy in France, and the minister of justice in the government of the Papal States, unde ...

, to administer the Papal States. He also showed himself hostile to Austrian

Austrian may refer to:

* Austrians, someone from Austria or of Austrian descent

** Someone who is considered an Austrian citizen

* Austrian German dialect

* Something associated with the country Austria, for example:

** Austria-Hungary

** Austria ...

influences, delighting Italian patriots, who hailed him as the coming redeemer of Italy. He once declared, "They want to make a Napoleon of me who am only a poor country parson."

In Pius' early years as pope, the government of the Papal States improved agricultural technology and productivity via farmer education in newly created scientific agricultural institutes. It abolished the requirements for Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

to attend Christian services and sermons and opened the papal charities to the needy amongst them. The new pope freed all political prisoners by giving amnesty to revolutionaries, which horrified the conservative monarchies in the Austrian Empire and elsewhere. "He was celebrated in New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

, London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

and Berlin

Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List of cities in Germany by population, population. With 3.7 million inhabitants, it has the List of cities in the European Union by population withi ...

as a model ruler."

Governmental structure

In 1848, Pius IX released a new constitution titled the " Fundamental Statute for the Secular Government of the States of the Church". The governmental structure of the Papal States reflected the dual spiritual-secular character of the papacy. The secular or laypersons were strongly in the majority with 6,850 persons versus 300 members of the clergy. Nevertheless, the clergy made key decisions and every job applicant had to present a character evaluation from his parish priest

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deity, deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in parti ...

to be considered.[Stehle 47]

Finance

Financial administration in the Papal States under Pius IX was increasingly put in the hands of laymen. The budget and financial administration in the Papal States had long been subject to criticism even before Pius IX. In 1850, he created a government finance body ("congregation") consisting of four laymen with finance backgrounds for the 20 provinces. After joining the Latin Monetary Union

The Monetary Convention of 23 December 1865 was a unified system of coinage that provided a degree of monetary integration among several European countries, initially Belgium, France, Italy and Switzerland, at a time when the circulation of bank ...

in 1866, the old Roman scudo

The Roman scudo (plural: ''scudi romani'') was the currency of the Papal States until 1866. It was subdivided into 100 baiocchi (singular: ''baiocco''), each of 5 quattrini (singular: ''quattrino''). Other denominations included the ''grosso'' of ...

was replaced by the new papal lira

The lira was the currency of the Papal States between 1866 and 1870. It was subdivided into 20 ''soldi'', each of 5 ''centesimi''.

History

In 1866 Pope Pius IX, whose temporal domain had been reduced to only the province of Latium, decided to ma ...

.

Commerce and trade

Pius IX is credited with systematic efforts to improve manufacturing and trade by giving advantages and papal prizes to domestic producers of wool

Wool is the textile fiber obtained from sheep and other mammals, especially goats, rabbits, and camelids. The term may also refer to inorganic materials, such as mineral wool and glass wool, that have some properties similar to animal w ...

, silk and other materials destined for export. He improved the transportation system by building roads, viaducts, bridges and seaport

A port is a maritime facility comprising one or more wharves or loading areas, where ships load and discharge cargo and passengers. Although usually situated on a sea coast or estuary, ports can also be found far inland, such as Hamburg, Manc ...

s. A series of new railway links connected the Papal States to northern Italy. It soon became apparent that the Northern Italians were more adept at economically exploiting the modern means of communication than the inhabitants in central and Southern Italy.

Justice

The justice system of the Papal States was subject to much criticism, not unlike the justice systems in the rest of Italy. Legal books were scarce, standards inconsistent, and judges were often accused of favoritism. In the Papal States and throughout Italy, organized criminal gangs threatened commerce and travelers, engaging in robbery and murder at will.

Military

The Papal army in 1859 had 15,000 soldiers. A separate military body, the elite

The Papal army in 1859 had 15,000 soldiers. A separate military body, the elite Swiss Guard

The Pontifical Swiss Guard,; ; ; ; , %5BCorps of the Pontifical Swiss Guard%5D. ''vatican.va'' (in Italian). Retrieved 19 July 2022. also known as the Papal Swiss Guard or simply Swiss Guard,Swiss Guards , History, Vatican, Uniform, Require ...

, served as the Pope's personal bodyguard.

Universities

The two papal universities in Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

and Bologna

Bologna ( , , ; ; ) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in northern Italy. It is the List of cities in Italy, seventh most populous city in Italy, with about 400,000 inhabitants and 150 different nationalities. Its M ...

suffered much from revolutionary activities in 1848 but their standards in the areas of science, mathematics, philosophy and theology were considered adequate. Pius recognized that much had to be done and instituted a reform commission in 1851. During his tenure, Catholics and Protestants

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

collaborated to found a school in Rome to study international law and train international mediators committed to conflict resolution. There was one newspaper, '' Giornale di Roma'', and one periodical, ''La Civiltà Cattolica

''La Civiltà Cattolica'' ( Italian for ''Catholic Civilization'') is a periodical published by the Jesuits in Rome, Italy. It has been published continuously since 1850 and is among the oldest of Catholic Italian periodicals. All of the journa ...

'', run by Jesuits

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

.

Arts

Like most of his predecessors, Pius IX was a patron of the arts. He supported architecture, painting, sculpture, music, goldsmith

A goldsmith is a Metalworking, metalworker who specializes in working with gold and other precious metals. Modern goldsmiths mainly specialize in jewelry-making but historically, they have also made cutlery, silverware, platter (dishware), plat ...

s, coppersmith

A coppersmith, also known as a brazier, is a person who makes artifacts from copper and brass. Brass is an alloy of copper and zinc. The term "redsmith" is used for a tinsmith that uses tinsmithing tools and techniques to make copper items.

Hi ...

s, and more, and handed out numerous rewards to artists. Much of his efforts went to renovate and improve churches in Rome and the Papal States. He ordered the strengthening of the Colosseum

The Colosseum ( ; , ultimately from Ancient Greek word "kolossos" meaning a large statue or giant) is an Ellipse, elliptical amphitheatre in the centre of the city of Rome, Italy, just east of the Roman Forum. It is the largest ancient amphi ...

, which was feared to be on the verge of collapse. Huge sums were spent in the excavation of the Christian Catacombs of Rome

The Catacombs of Rome () are ancient catacombs, underground burial places in and around Rome, of which there are at least forty, some rediscovered since 1578, others even as late as the 1950s.

There are more than fifty catacombs in the underg ...

, for which Pius created a new archaeological commission in 1853.

Jews

The Papal States were a theocracy

Theocracy is a form of autocracy or oligarchy in which one or more deity, deities are recognized as supreme ruling authorities, giving divine guidance to human intermediaries, with executive and legislative power, who manage the government's ...

in which the Catholic Church and its members had far more rights than other religions. Pius IX's religious policies became increasingly reactionary over time. At the beginning of his pontificate, together with other liberal measures, Pius opened up the Jewish ghetto in Rome, freeing Jews to reside elsewhere. In 1850, after French troops defeated the revolutionary Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( ) was the era of Ancient Rome, classical Roman civilisation beginning with Overthrow of the Roman monarchy, the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom (traditionally dated to 509 BC) and ending in 27 BC with the establis ...

and returned him from exile, the Pope reversed the Republic's religious freedom laws and issued a series of anti-liberal measures, including re-instituting the Jewish ghetto.

In a highly publicized case

Case or CASE may refer to:

Instances

* Instantiation (disambiguation), a realization of a concept, theme, or design

* Special case, an instance that differs in a certain way from others of the type

Containers

* Case (goods), a package of relate ...

from 1858, the police of the Papal States seized a 6-year-old Jewish boy, Edgardo Mortara, from his parents. A Christian servant girl unrelated to the family claimed she had informally baptized

Baptism (from ) is a Christian sacrament of initiation almost invariably with the use of water. It may be performed by sprinkling or pouring water on the head, or by immersing in water either partially or completely, traditionally three ...

him during an illness six years prior, fearing he would die. This had made the child legally a Christian convert, and Papal law forbade Christians from being raised by Jews, even their own parents. The incident provoked widespread outrage amongst liberals, both Catholic and non-Catholic, and contributed to the growing anti-papal sentiment in Europe. The boy was raised in the papal household

The papal household or pontifical household (usually not capitalized in the media and other nonofficial use, ), called until 1968 the Papal Court (''Aula Pontificia''), consists of dignitaries who assist the pope in carrying out particular ceremon ...

, and was eventually ordained a priest at age 21.

Policies toward other nations

Pius IX was the last pope who also functioned as a secular ruler and the monarch of the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; ; ), officially the State of the Church, were a conglomeration of territories on the Italian peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope from 756 to 1870. They were among the major states of Italy from the 8th c ...

, ruling over some 3 million subjects from 1846 to 1870, when the newly founded Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy (, ) was a unitary state that existed from 17 March 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 10 June 1946, when the monarchy wa ...

seized the remaining areas of the Papal States by force of arms. Contention between Italy and the Papacy was only resolved legally by the 1929 Lateran Treaty

The Lateran Treaty (; ) was one component of the Lateran Pacts of 1929, agreements between Italy under Victor Emmanuel III and Benito Mussolini and the Holy See under Pope Pius XI to settle the long-standing Roman question. The treaty and ass ...

(''Lateran Pacts'' or ''Lateran Accords'') between the Kingdom of Italy under Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his overthrow in 194 ...

and the Holy See

The Holy See (, ; ), also called the See of Rome, the Petrine See or the Apostolic See, is the central governing body of the Catholic Church and Vatican City. It encompasses the office of the pope as the Bishops in the Catholic Church, bishop ...

, the latter receiving financial compensation for the loss of the Papal States and recognition of the Vatican City State as the sovereign independent territory of the Holy See.

Italy

Though he was well aware upon his accession of the political pressures within the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; ; ), officially the State of the Church, were a conglomeration of territories on the Italian peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope from 756 to 1870. They were among the major states of Italy from the 8th c ...

, Pius IX's first act was a general amnesty

Amnesty () is defined as "A pardon extended by the government to a group or class of people, usually for a political offense; the act of a sovereign power officially forgiving certain classes of people who are subject to trial but have not yet be ...

for political prisoner

A political prisoner is someone imprisoned for their political activity. The political offense is not always the official reason for the prisoner's detention.

There is no internationally recognized legal definition of the concept, although ...

s, despite the potential consequences. The freed revolutionaries resumed their previous political activities, and his concessions only provoked greater demands as patriotic Italian groups sought not only a constitutional government – to which he was sympathetic – but also the unification of Italy

The unification of Italy ( ), also known as the Risorgimento (; ), was the 19th century Political movement, political and social movement that in 1861 ended in the Proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, annexation of List of historic states of ...

under his leadership and a war of liberation to free the northern Italian provinces from the rule of Catholic Austria.

By early 1848, all of Western Europe began to be convulsed in various revolutionary movements

A revolutionary movement (or revolutionary social movement) is a specific type of social movement dedicated to carrying out a revolution.

Criteria

Charles Tilly defines it as "a social movement advancing exclusive competing claims to control o ...

. The Pope, claiming to be above national interests, refused to go to war with Austria, which reversed Pius' popularity in his native Italy. In a calculated, well-prepared move, Prime Minister Rossi was assassinated on 15 November 1848, and in the days following, the Swiss Guard

The Pontifical Swiss Guard,; ; ; ; , %5BCorps of the Pontifical Swiss Guard%5D. ''vatican.va'' (in Italian). Retrieved 19 July 2022. also known as the Papal Swiss Guard or simply Swiss Guard,Swiss Guards , History, Vatican, Uniform, Require ...

s were disarmed, making the Pope a prisoner in his palace. However, he succeeded in escaping Rome several days later.

A Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( ) was the era of Ancient Rome, classical Roman civilisation beginning with Overthrow of the Roman monarchy, the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom (traditionally dated to 509 BC) and ending in 27 BC with the establis ...

was declared in February 1849. Pius responded from his exile by excommunicating all participants. After the suppression of the republic later that year, Pius appointed a conservative government of three cardinals known as the Red Triumvirate to administer the Papal States until his return to Rome in April 1850. He visited the hospitals to comfort the wounded and sick, but he seemed to have lost both his liberal tastes and his confidence in the Romans, who had turned against him in 1848. Pius decided to move his residence from the Quirinal Palace

The Quirinal Palace ( ) is a historic building in Rome, Italy, the main official residence of the President of Italy, President of the Italian Republic, together with Villa Rosebery in Naples and the Tenuta di Castelporziano, an estate on the outs ...

inside Rome to the Vatican, where popes have lived ever since.

End of the Papal States

After defeating the Papal army on 18 September 1860 at the

After defeating the Papal army on 18 September 1860 at the Battle of Castelfidardo

The Battle of Castelfidardo took place on 18 September 1860 at Castelfidardo, a small town in the Marche region of Italy. It was fought between the Royal Sardinian Army – acting as the driving force in the war for Italian unification, against ...

, and on 30 September at Ancona

Ancona (, also ; ) is a city and a seaport in the Marche region of central Italy, with a population of around 101,997 . Ancona is the capital of the province of Ancona, homonymous province and of the region. The city is located northeast of Ro ...

, Victor Emmanuel II of Sardinia

Victor Emmanuel II (; full name: ''Vittorio Emanuele Maria Alberto Eugenio Ferdinando Tommaso di Savoia''; 14 March 1820 – 9 January 1878) was King of Sardinia (also informally known as Piedmont–Sardinia) from 23 March 1849 until 17 March ...

took all the Papal territories except Latium

Latium ( , ; ) is the region of central western Italy in which the city of Rome was founded and grew to be the capital city of the Roman Empire.

Definition

Latium was originally a small triangle of fertile, volcanic soil (Old Latium) on whic ...

with Rome and took the title King of Italy

King is a royal title given to a male monarch. A king is an absolute monarch if he holds unrestricted governmental power or exercises full sovereignty over a nation. Conversely, he is a constitutional monarch if his power is restrained by ...

. Rome itself was invaded on 20 September 1870 after a few-hours siege. Italy instituted the Law of Guarantees

The Law of Guarantees (), sometimes also called the Law of Papal Guarantees, was the name given to the law passed by the senate and chamber of the Parliament of the Kingdom of Italy, 13 May 1871, concerning the prerogatives of the Holy See, and th ...

(13 May 1871) which gave the Pope the use of the Vatican but denied him sovereignty over this territory, nevertheless granting him the right to send and receive ambassadors and a budget of 3.25 million lira

Lira is the name of several currency units. It is the current Turkish lira, currency of Turkey and also the local name of the Lebanese pound, currencies of Lebanon and of Syrian pound, Syria. It is also the name of several former currencies, ...

annually. Pius IX officially rejected this offer (encyclical ''Ubi nos'', 15 May 1871), since it was a unilateral decision which did not grant the papacy international recognition and could be changed at any time by the secular parliament.

Pius IX refused to recognize the new Italian kingdom, which he denounced as an illegitimate creation of revolution. He excommunicated the nation's leaders, including King Victor Emmanuel II, whom he denounced as "forgetful of every religious principle, despising every right, trampling upon every law," whose reign over Italy was therefore "a sacrilegious usurpation."

Mexico

In response to the upheavals faced by the Papal States during the 1848 revolutions, the

In response to the upheavals faced by the Papal States during the 1848 revolutions, the Mexican government

The Federal government of Mexico (alternately known as the Government of the Republic or ' or ') is the national government of the United Mexican States, the central government established by its constitution to share sovereignty over the republ ...

offered Pope Pius IX asylum, which the pope responded to by considering the creation of a Mexican cardinal and granting an award to President José Joaquín de Herrera

José Joaquín Antonio Florencio de Herrera y Ricardos (February 23, 1792 – February 10, 1854) was a Mexican statesman who served as president of Mexico three times (1844, 1844–1845 and 1848–1851), and as a general in the Mexican Army d ...

. With French Emperor Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles-Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was President of France from 1848 to 1852 and then Emperor of the French from 1852 until his deposition in 1870. He was the first president, second emperor, and last ...

's military intervention in Mexico and establishment of the Second Mexican Empire

The Second Mexican Empire (; ), officially known as the Mexican Empire (), was a constitutional monarchy established in Mexico by Mexican monarchists with the support of the Second French Empire. This period is often referred to as the Second ...

under Maximilian I in 1864, the church sought relief from a friendly government after the anti-clerical actions of Benito Juárez

Benito Pablo Juárez García (; 21 March 1806 – 18 July 1872) was a Mexican politician, military commander, and lawyer who served as the 26th president of Mexico from 1858 until his death in office in 1872. A Zapotec peoples, Zapotec, he w ...

, who had suspended payment on foreign debt and seized ecclesial property.

Pius blessed Maximilian and his wife Charlotte of Belgium

Charlotte of Mexico (; ; 7 June 1840 – 19 January 1927), known by the Spanish version of her name, Carlota, was by birth a princess of Belgium and member of the House of Wettin in the branch of House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, Saxe-Coburg ...

before they set off for Mexico to begin their reign. But the friction between the Vatican and Mexico would continue with the new emperor when Maximilian insisted on freedom of religion, which Pius opposed. Relations with the Vatican would only be resumed when Maximilian sent the recently converted American Catholic priest Father Agustin Fischer to Rome as his envoy.

Contrary to Fischer's reports back to Maximilian, the negotiations did not go well and the Vatican would not budge. Maximilian sent his wife Charlotte to Europe to plead with Napoleon III against the withdrawal of French troops from Mexico. After unsuccessful meetings with Napoleon III, Charlotte travelled to Rome to plead with Pius in 1866. As the days passed, Charlotte's mental state deteriorated. She sought refuge with the pope, and she would eat and drink only what was prepared for him, fearful that everything else might be poisoned. The pope, though alarmed, accommodated her, and even agreed to let her stay in the Vatican one night after she voiced anxiety about her safety. She and her assistant were the first women to stay the night inside the Vatican.

England and Wales

England for centuries was considered missionary territory for the Catholic Church. In the wake of Catholic emancipation in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

(which included all of Ireland), Pius IX changed that with the bull ''Universalis Ecclesiae

was a papal bull of 29 September 1850 by which Pope Pius IX recreated the Roman Catholic diocesan hierarchy in England, which had been extinguished with the death of the last Marian bishop in the reign of Elizabeth I. New names were given to ...

'' (29 September 1850). He re-established the Catholic hierarchy in England and Wales, under the newly appointed Archbishop and Cardinal Nicholas Wiseman

Nicholas Patrick Stephen Wiseman (3 August 1802 – 15 February 1865) was an English Roman Catholic prelate who served as the first Archbishop of Westminster upon the re-establishment of the Roman Catholic hierarchy in England and Wales in 1 ...

with 12 additional episcopal seats: Southwark

Southwark ( ) is a district of Central London situated on the south bank of the River Thames, forming the north-western part of the wider modern London Borough of Southwark. The district, which is the oldest part of South London, developed ...

, Hexham

Hexham ( ) is a market town and civil parish in Northumberland, England, on the south bank of the River Tyne, formed by the confluence of the North Tyne and the South Tyne at Warden nearby, and close to Hadrian's Wall. Hexham was the administra ...

, Beverley

Beverley is a market town and civil parish in the East Riding of Yorkshire, England. It is located north-west of Hull city centre. At the 2021 census the built-up area of the town had a population of 30,930, and the smaller civil parish had ...

, Liverpool

Liverpool is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. It is situated on the eastern side of the River Mersey, Mersey Estuary, near the Irish Sea, north-west of London. With a population ...

, Salford

Salford ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city in Greater Manchester, England, on the western bank of the River Irwell which forms its boundary with Manchester city centre. Landmarks include the former Salford Town Hall, town hall, ...

, Shrewsbury

Shrewsbury ( , ) is a market town and civil parish in Shropshire (district), Shropshire, England. It is sited on the River Severn, northwest of Wolverhampton, west of Telford, southeast of Wrexham and north of Hereford. At the 2021 United ...

, Newport, Clifton, Plymouth

Plymouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Devon, South West England. It is located on Devon's south coast between the rivers River Plym, Plym and River Tamar, Tamar, about southwest of Exeter and ...

, Nottingham

Nottingham ( , East Midlands English, locally ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority area in Nottinghamshire, East Midlands, England. It is located south-east of Sheffield and nor ...

, Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands (county), West Midlands, within the wider West Midlands (region), West Midlands region, in England. It is the Lis ...

, and Northampton

Northampton ( ) is a town and civil parish in Northamptonshire, England. It is the county town of Northamptonshire and the administrative centre of the Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority of West Northamptonshire. The town is sit ...

. Some violent street protests against the "papal aggression" resulted in the passage of the Ecclesiastical Titles Act 1851, which forbade any Catholic bishop to use an episcopal title "of any city, town or place, or of any territory or district (under any designation or description whatsoever), in the United Kingdom".repeal

A repeal (O.F. ''rapel'', modern ''rappel'', from ''rapeler'', ''rappeler'', revoke, ''re'' and ''appeler'', appeal) is the removal or reversal of a law. There are two basic types of repeal; a repeal with a re-enactment is used to replace the law ...

ed twenty years later.

Ireland

Pius donated money to Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

during the Great Famine. In 1847, he addressed the suffering Irish people in the encyclical '' Praedecessores nostros''.

Netherlands

The Dutch government instituted religious freedom for Catholics in 1848. In 1853, Pius erected the Archdiocese of Utrecht and four dioceses in Haarlem

Haarlem (; predecessor of ''Harlem'' in English language, English) is a List of cities in the Netherlands by province, city and Municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality in the Netherlands. It is the capital of the Provinces of the Nether ...

, Den Bosch

s-Hertogenbosch (), colloquially known as Den Bosch (), is a List of cities in the Netherlands by province, city and List of municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality in the Netherlands with a population of 160,783. It is the capital of ...

, Breda

Breda ( , , , ) is a List of cities in the Netherlands by province, city and List of municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality in the southern part of the Netherlands, located in the Provinces of the Netherlands, province of North Brabant. ...

, and Roermond

Roermond (; or ) is a city, municipality, and diocese in the Limburg (Netherlands), Limburg province of the Netherlands. Roermond is a historically important town on the lower Roer on the east bank of the river Meuse. It received City rights i ...

under it. As in England, this resulted in a brief popular outburst of anti-Catholic sentiment.

Spain

Traditionally Catholic Spain offered a challenge to Pius IX as anti-clerical governments came to power in 1832, resulting in the expulsion of religious orders; the closing of convents, Catholic schools and libraries; the seizure and sale of churches and religious properties; and the inability of the church to fill vacant dioceses. In 1851, Pius IX concluded a concordat with Queen Isabella II